A few months ago a Facebook advertisement piqued my interest about how the company was leveraging my user data to target ads in my feed. What began as a passing curiosity about how the company targets advertising, turned into a deep dive at big tech's hidden and unregulated practices. The research led me to construct an experiment that exposed not only a deep level of corporate surveillance into our everyday lives, but also a cross-platform and cross-company effort to integrate our personal data, and use it to manipulate user behavior.

"Information is the oil of the 21st century, and analytics is the combustion engine," Peter Sondergaard of Research at Gartner, Inc, said back in 2011. By 2017 this was true, as data surpassed oil as the world's top commodity. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2017/05/06/the-worlds-most-valuable-re...

I knew already that the things I liked, and the things I followed effected the stream of ads I would receive on Facebook. When the company added emojis a few years back of an angry face, of a crying face, of a heart, that was part of honing their marketing game. Each and every day the company is trying to push deeper into our personal lives, and use our personal data to profit off of advertisers who recognize the value of precision advertisement targeting.

I had used this type of advertisement targeting while I was the publisher of a San Francisco-based news organization several years ago. I was surprised at the time at the great results we had spending $5 here and $10 there on what Facebook calls a “sponsored post” to help us connect to our audience.

But, when my sister messaged me last summer on Facebook that she had set aside some of my late grandmother's china for me to have and included a picture of the pattern, I immediately began receiving ads for the same antique Japanese dishes. The platform had recognized the pattern, filched from an image posted to my personal messages, and fed me ads that they knew, by my activity, held a special importance for me.

It was a bit startling. Not only were they in my private messages looking for user information, they had matched an image.

The incident made me start to pay closer attention to the reach Facebook and other tech giants have into my personal data. I began looking for correlations in my online data footprint and what was advertised to me on Facebook.

The platform, and the social media industry in general, currently operates outside of any meaningful government regulation.

Even after it was revealed in 2014 that Facebook, in conjunction with Cornell and the University of California, had conducted an “emotional contagion” experiment on 689,000 users without their consent https://www.theguardian.com/technology/2014/jun/29/facebook-users-emotio..., nothing was done to regulate the industry in the United States. The now well-known experiment focused on Facebook's ability to alter people's emotional state to make them happier or sadder, depending on the specific diet of information that Facebook tailored to individuals' feeds.

It was perhaps the largest experiment ever conducted without people's consent, and the most startling finding was that they were able to conduct the experiment without users being aware that they were being manipulated.

Since the days of the Dot Com Crash in the early 2000's, the financial model of big tech has shifted to user data being the true commodity of online platforms. An opaqueness surrounding the handling of user data became essential to the industry's ability to operate – and to profit.

The “round gable vent”

“Search your feelings; you know it to be true!” Darth Vader, The Empire Strikes Back

So with eyes wide open to the industry's desire to keep the nature of its operations secret, and simultaneously trying to weed out my own confirmation bias, I set about trying to see through the digital veil obscuring industry practice.

It's a lot to sort through, as I was bombarded with advertisement after advertisement, while trying to parse why I was receiving them. Was it from a post I liked? Was if from a group I joined? Was it a guess based on the articles I had clicked through?

And that's when I got served an ad from Home Depot, advertising a round gable vent. The ad startled me to the core.

A little background. As everyone should know by now, journalism is a suffering industry, where employment has become scarce and remissions small.

As a result, for the last 20 years, like many of my colleagues, I've had to supplement my income. To do this I swing a hammer as an independent contractor. A construction project I was working on last month required me to special order round gable vent to replace an old one that had rotted out. I searched the item on Google, and then used their shopping tab. I found what I was looking for immediately and followed a link to Lowes' website. I ordered it with my VISA debit card online for delivery to my local Lowes.

So when Home Depot's ad crossed my feed I got the first definitive peek behind the wizard's curtain that I had been scanning for. For about two weeks after my order, Home Depot targeted an ad at me on Facebook's platform, for -- a round gable vent.

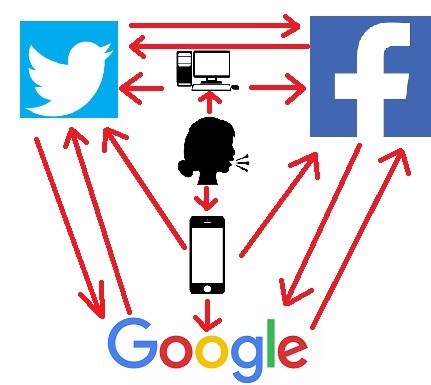

I was shocked; I was horrified. The data had clearly done what every big tech company insists does not happen; it crossed the boundary between my Google search (or Lowes purchase) and onto a completely different platform – Facebook. I began to pay very close attention now. I began to take notes. I began to take screen shots. I began to ask deeper questions about cross-platform sharing of my personal data.

My research brought me into the world of the Data Transfer Project.

I was expecting a secret agreement, a backdoor channel between the companies. As it turns out, the Data Transfer Project is an open source project between the world's largest tech companies to share your personal data with each other. However, what I found has not been publicly announced. The project is open source and you can track its progress yourself at GitHub https://github.com/google/data-transfer-project

Google, Microsoft, Facebook, and Twitter all signed on to begin creating it in the summer of 2018. Apple joined in as of summer, 2019. https://www.theverge.com/2019/7/30/20746868/apple-data-transfer-project-...

The scant news of the agreement passed by as another blip in the long march towards big tech dominance and a corporate parallel of the government's total information awareness model, which seeks to store and analyze all digital data. Nobody questioned what would become of the project. No regulators poured over the agreement. No tech journal sounded alarm bells over its implications. It seemed natural that the world's largest tech companies needed infrastructure and protocols to access each others' data – their data about you and everyone else.

It took time to put together the back-end coding to make a data pipeline run, and special infrastructure for the vast streams of data to travel efficiently back and forth between the companies.

While much of the initial work was back-end, the companies have stated that they are in the consumer-facing products phase of the project now. And even though the companies still won't be transparent about how your personal data is being shared, we are starting to see the results of the project.

“We’re really encouraged by the progress the Data Transfer Project has made since we announced it last year, and look forward to rolling out our first user-facing features in the coming months,” said Jessie Chavez, Google’s lead for the Data Transfer Project in August of 2019.

An unregulated industry

“Quis custodiet ipsos custodes?” (Who watches the watchers?) – Satires

Regulation always takes time to catch up to technology. The automobile, the true economic engine of the industrial era, is recognized to have gone into production in 1885, though the concept had been experimented with for decades before.

For nearly a century, the government looked on silently, and the auto industry resisted any notion of regulatory pressure, as body after body was projected through windshields to be retrieved off the roadways by emergency workers, limp and lifeless.

Federal law requiring seat belts as a standard feature in all cars manufactured and sold in the United States took effect in 1968.

Society's pace of innovation in the digital age has progressed on an exponential curve known as Moore's law, with computing doubling in capacity roughly every 18 months. The government's ability to keep up and regulate the tech industry has fallen further and further behind. There are fundamental problems in how our rights were guaranteed (and not) over 200 years ago when the Bill of Rights was adopted.

“We do not have an omnibus privacy legislation at the federal level,” David Vladeck, former director of the Federal Trade Commission’s Bureau of Consumer Protection, told Wired magazine in March of 2018. https://www.wired.com/story/what-would-regulating-facebook-look-like/

“We don’t have a statute that recognizes generally that privacy is a right that’s secured by federal law.”

The first serious look into regulating how technology companies use personal data arrived with revelations that Cambridge Analytica leveraged personal user data obtained through Facebook to target voters in the 2016 presidential election to either vote for President Trump, or failing that, to stay home and not vote at all.

The methods built on the knowledge gained though Facebook's vast emotional contagion experiment. And while the attention has been focused on Cambridge Analytica, that company was by-in-large acting the same as any modern public relations company. It was big tech's vast collection of data that Cambridge Analytica was tapping into.

Politicians for the first time took notice of the threat that leveraging the troves of stored personal user data posed to democracy itself – or at least took note that their own political career could be cut short through such methods.

While many fingers pointed at Russia, it has slowly percolated into the public's consciousness that the threat is domestic, and we are participants.

“One business practice I want to eliminate is the use of microtargeting in political advertising,” writes former Facebook executive Roger Mcnamee, author of Zucked. “Facebook, in particular, enables advertisers to identify an emotional hot button for individual voters that can be pressed for electoral advantage, irrespective of its relevance to the election. Candidates no longer have to search for voters who share their values. Instead they can invert the model, using microtargeting to identify whatever issue motivates each voter and play to that.”

Senate minority leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) has at times been a proponent of regulating how big tech uses these advanced marketing techniques in the political sphere, but is cautious about applying rules to consumer-based advertising, fearing unintended consequences on freedom of speech.

But enacting regulations on these companies becomes problematic because of how their consumer surveillance efforts interweave with the operations of American intelligence agencies governmental surveillance efforts. Like Cambridge Analytica, these agencies are leveraging data from big tech for their own purposes.

Most of the online discussion of this topic is woefully out of date. Searching Facebook's “help community” forum on the topic “does Facebook monitor my Google searches?” https://www.facebook.com/help/community/question/?id=10151465451796820 I'm directed to a post from 2012, which can be summed up as, nope, you're crazy.

And it's easy to feel that way looking online for answers. By-enlarge articles on this topic that aggregate in searches are from early 2018 (before the massive data share agreements between the tech giants, and long before any front-end roll out resulting from the program). They say the same thing. No -- and you may be crazy.

It's enough to make a person feel crazy. Just last month (December 2019), the nation's most trusted news source https://www.pbs.org/about/blogs/news/for-the-16th-consecutive-year-ameri... , PBS, stated emphatically in a Frontline documentary titled In the Age of AI that this type cross-platform, cross-device advertising is not happening: “The companies say they are not using the data to target ads, but helping the AI to improve the user experience.”

Internet of things

“It was terribly dangerous to let your thoughts wander when you were in any public place or within range of a telescreen. The smallest thing could give you away.” George Orwell, 1984

The smart TV, smart appliances, smart video door bells, even your high-end coffeemaker are all suspect.

While Google, Apple and Amazon all say that their microphones are not constantly active, this is a bit of a misnomer. Both the Google Assistant, Apple's Siri and Amazon's Alexa systems are activated by “trigger” words or phrases. “OK, Google,” for example activates the Google Assistant. But the logic of the company's claims simply does not follow. If the microphone is inactive, how would it recognize a voice command such as “OK, Google” in the first place?

What the companies are saying, in an obscuring way, is that voice data overheard in the absence of trigger phrases is discard. They conflate this with an inactive microphone. Voice data following a trigger word is logged into your personal data archive.

While activation triggers like “OK, Google” are publicly acknowledged triggers, many worry that there could be thousands of trigger phrases that alert the system to start logging the data.

The home pizza oven experiment

“The slow blade penetrates the shield.” Gurney Halleck, Frank Herbert's Dune.

As I systematically delved deeper into what triggers specific ads to appear in my Facebook feed, I noticed something startling happen. I was on the phone with a friend, and he suggested that I should pick up a CNC lathe for my workshop. I had been building more and more furniture on custom order, and he suggested that a machine that could be programed to do the work for me would up my productivity. I'm no Luddite, so I discussed the idea of purchasing one. We talked price point, brand, and what software interface was ideal. Three hours later, I was advertised a CNC lathe in my feed.

The ad stopped me in my tracks. This was not a search term I entered into either Google or Facebook, it was a private phone conversation with a friend. I called back and we devised an experiment, one that would put to rest any lingering doubt that key phrases from my private phone conversations were ending up advertised back to me in my Facebook advertising feed.

I had already realized that people are skeptical of the idea that cross-platform, cross-device advertising of this type is happening. When I pointed out on an acquaintance's Facebook thread that this seems to be the case, a debate over it led to me being “unfriended” after I disputed the voracity of a claim in Wired magazine, one of the tech industry's most trusted sources, which said it was not happening. When I tried to point out that, like much written on the topic, the article was from early 2018, and that things had changed, I was lambasted as a conspiracy theorist and dumped.

I knew then that I would need a method to prove what I was saying.

The experiment we constructed was simple. I called it the “home pizza oven” experiment. My friend would pass me a term through encrypted communication (our first attempt was a home pizza oven), and I would call back on an open line and say the term. We tried to tailor our conversation to what we thought typical trigger phrases could be … “I should buy,” “I want,” “love to have,” “need to find.” Our conversation about home pizza ovens lasted about 5 minutes.

We used some parameters for the phrase. We didn't want a phrase that either of us had ever searched or a product either of us ever expressed interest in. We also wanted a clear consumer product that some company could conceivably be running a Facebook ad on.

Each time we ran he experiment, it took about 3 hours for me to see the results in my Facebook feed. It never appeared in his feed.

But, he is a trained in computer security, and keeps cleaner data habits than I do. For example, I surf the web on my phone (an LG serviced by T-mobile). I use my Google account from my phone. He doesn't use a Google account at all. Most importantly, as I have found out in researching this article, I verified my phone number with Google as an account recovery method. This is something Google had pushed to me for a long time, and a few months ago, after years of refusing, I relented and gave them the verification.

I followed the advice by a headline printed earlier this year in Forbes when considering the issue of giving Google my phone number titled Google wants your phone number, should you provide it? https://www.forbes.com/sites/daveywinder/2019/05/19/google-wants-your-ph...

The article starts out, “There's a rule of thumb that if an article poses a question in the headline then the answer is always no … Today is not one of those days, it's an exception to the usual rule in that I'm suggesting in response to Google requesting your phone number that it might just be a very good idea to hand it over.”

I trusted Forbes (mostly), I trusted Google (mostly), so I took the advice.

Bad move. Increasingly we base our trust online in brand-based trust, rather than thinking though the implications for ourselves. Increasingly these brands leverage this trust to betray us in just the ways we feared in the first place.

From what I have been able to surmise, the verification of my phone number with Google positively linked my identity to my phone data, and then out it goes as part of the personal data package I would later learn Google is sharing actively with Facebook.

It can be assumed that the lag time of 3 to 4 hours I experienced for the ad to appear is intentional. There is nothing about the data that takes that long to transfer. It is part of keeping the phenomenon, which once again the companies continue to insist does not happen, less than obvious. If the results were to appear immediately, customers might react negatively.

A caveat about what I noticed. It is possible that I'm in an early roll out group. As we have seen with the mood contagion experiment, Facebook has singled out sample groups of its vast user base to experiment on already. Perhaps I am in such a group. Buy what the blind nature of the experiment confirms is that Facebook, Google, and/or a third party, are translating voice to text, and then marketing to us both across platforms and across devices.

Should we worry?

“I know I've made some very poor decisions recently, but I can give you my complete assurance that my work will be back to normal.” HAL 9000, 2001 Space Odyssey.

I began to redouble my efforts to see connections in my advertising, and continuing to try to weed out ads that had an in-platform explanation. I scrolled and scrolled looking for the connections.

I also began to hammer away at Google searches that would confirm my findings. Very little was out there that made the claim I'm making.

But as I dug into thoroughly researching the topic, I realized that my research itself was tainting the experiment. As I explored how the ads worked behind the scenes, the advertising in my Facebook feed began to be dominated by advertisements from Facebook themselves – on how they could help my business grow using Facebook ads. It was like peeking at a quantum physics experiment – the act of observation was changing the results, like a digital Heisenberg Uncertainty Principal. And of course pounding away on keyword searches about Facebook advertising had led them to advertise that very advertising at me. But something more troubling also appeared.

I was using the platform far more that I was accustomed too, and Facebook noticed my change of habit. My ad feed became dominated by ads wondering if I was manic.

Maybe I was? There is nothing that kicks a journalist into high gear like being hot on the trail of a story that has not been broken.

Something deeper about this suggestion troubled me though. The mood contagion experiment, where Facebook intentionally gaslighted more than a half of million people, to see what results it could produce.

Facebook appeared to be not just tailoring its ads to what I typed in Google, or what I said when I was on a private phone call. It was tailoring its ads to what it thought my current emotional state was.

While Facebook denies advertising based on users' emotional state, the Irish government has brought a lawsuit against the company that seeks to prove they engage in the practice, and to regulate against it.

I had to stop the experiment, and walk away with the results I had.

How far is too far?

“There will come a time when it isn't 'They're spying on me through my phone' anymore. Eventually, it will be 'My phone is spying on me'.” - Philip K. Dick. Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?

On one hand there are obvious conveniences to the platform connecting customers seamlessly to the products that they want. There is also an economic efficacy gained that has been important to the post-great recession economy.

But society should tread carefully as we enter what is becoming known as “surveillance capitalism.” According to Harvard professor Shoshana Zuboff, who coined the term, surveillance capitalism “must be operations that are engineered as undetectable, indecipherable, cloaked in rhetoric, that aim to misdirect obfuscate and just downright bamboozle all of us all the time.”

There is a growing awareness in society that we are being monitored at any given moment, and it's leading to a type of digital Panopticon effecting people's behaviors. We are only beginning to grapple with the implications.

While the political world takes a narrow focus, exploring how this all effects elections, they are largely sidestepping the issue of how this effects society at large.

We are only now beginning to wake up to the deal we made for free services on the internet, and the price of this deal is more far reaching than society has yet come to grips with.

A recently released report by Amnesty International titled Surveillance Giants, which sounds the alarm stating emphatically that Facebook and Google’s pervasive surveillance poses an unprecedented danger to human rights. The report urges governments worldwide to take immediate action to regulate big data.

“People who are under constant surveillance face pressure to conform. Privacy’s key role in shaping different identities encourages a diversity of culture. Having layered identities is often the core condition of any minority group seeking to live, work, and subsist in a dominant culture,” The report states.

“This extraction and analysis of people’s personal data on such an unprecedented scale is incompatible with every element of the right to privacy, including the freedom from intrusion into our private lives, the right to control information about ourselves, and the right to a space in which we can freely express our identities.”